Over the last two months, we've reviewed the seven fundamental Quality Management Principles defined in ISO 9000:2015: Customer focus, Leadership, Engagement of people, the Process approach, Improvement, Evidence-based decision making, and Relationship management. We started by investigating why Quality Management should be based on these seven principles in particular, and not some others instead. And then we looked at each principle, one by one, to understand what it means, why we should care, and what we can do about it. I've found it interesting, and I hope you have.

But there is one fact we haven't addressed yet. These principles are the conceptual foundation on which the concepts of Quality and Quality management are built. And they are spelled out in ISO 9000:2015, clause 2.3. But the ISO 9000 standard is still undergoing regular revision, which means that these concepts are still being refined and improved. In a future edition, the committee responsible for the document (ISO TC176) might even decide to add another basic principle, or change the foundations in other ways. All of this is still being defined—actively, here and now, in the present day.

So I have to ask: Why are we only defining these concepts now? It's not like Quality is a new idea. People have known the difference between doing good work and doing bad work as long as there have been people doing any work at all. The Code of Hammurabi contains provisions for product liability, in case of poor workmanship.* Even Plato discusses product Quality incidentally, while trying to enquire what makes things good or beautiful.** So why didn't someone work out the conceptual foundations of Quality way back in Antiquity? If Quality is important—which it is!—and if it has been known for so long, why didn't Aristotle write about it?

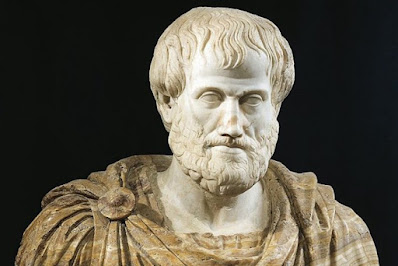

|

Aristotle (marble portrait bust, Roman copy of a Greek original).

He never discusses Quality Management. |

Let's take another look at that list of seven principles, in search of a clue.

Three of them are ancient

There is no question that the last three principles in the list date from Antiquity. The Stoics taught methods for systematic personal Improvement covering all aspects of life. The whole focus of ancient philosophy was in support of Evidence-based decision making, instead of following rules supported by tradition or public opinion. And the idea of Relationship management is at least as old as the Golden Rule. If these had been the only foundations needed for the concept of Quality, it certainly would have been discussed in ancient times.

One is very modern

At the other extreme, the Process approach was created by Walter Shewhart in the first half of the twentieth century. Shewhart distilled the experience of a century of industrialists who had implemented more or less formal procedures in their factories. His work also drew on earlier developments in statistics, such as Charles S. Peirce's application of statistics to the design of experiments, and Francis Galton's development of standard deviation and regression analysis. It is even possible that Shewhart's work might have been influenced by the process metaphysics of Alfred North Whitehead.*** But in any event, from the perspective of intellectual history the Process approach is very new.

And the other three have grown on us

The history of the first three principles, though, is more interesting.

Leadership and the Engagement of people

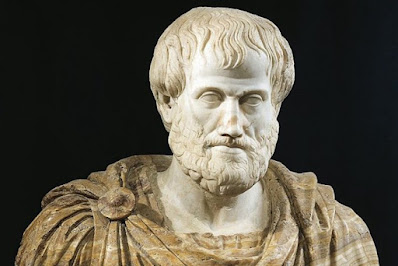

|

Frederick W. Taylor, founder of

"scientific management." |

Leadership and Engagement of people have both been known since ancient times, but not in the way they appear here.**** In the past, studies of leadership—from Sun Tzu's Art of War and Xenophon's Education of Cyrus through Machiavelli's The Prince—were written about military or political organizations. By contrast, the study of business or factory management is generally supposed to have started with Frederick W. Taylor, who published Shop Management in 1903, and Principles of Scientific Management in 1911. (Some sources identify additional pioneers besides Taylor in the study of management, but nearly all these pioneers lived—like he did—in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.)

What accounts for the difference? Why is there a gap of more than two millennia between the first studies of princes and the first studies of managers? At the highest level of abstraction, princes and managers are engaged in the same kind of job: getting other people to do things. Of course their methods are different, as are the details of what they want done. But for the current question, I think the most relevant difference is that by the late nineteenth century, managers were becoming far more common than they used to be.

It's true that there were large-scale business concerns in Antiquity: the Roman latifundia covered hundreds or thousands of acres and employed hundreds of slaves. And all through the years since, there were always a few large businesses. But for centuries they represented a small share of the economy. Most people were farmers or sole proprietors. It is only in the last—oh, let's say 150 or 200 years—that things have changed significantly.

Two hundred years ago, if you met someone new and wanted to know about his work, you might ask, "What do you do?" Today, the question is at least as likely to be "Who do you work for?" In the modern economy, nearly everyone is an employer or an employee—or sometimes, both at once. And therefore, the twin topics of Leadership and Engagement of people have taken on an importance in everyone's daily work life that they never had before. As I say, they have grown on us.

Customer focus

We see exactly the same evolution in the concept of Customer focus.

Of course the basic idea that a customer should get what he pays for is very old. In the past, that principle would have been seen as an instance of the concept Justice.

But Customer focus involves so much more than that! As we saw back in March, Customer focus requires you to identify who your customers are, and then to understand what they really need. This requirement is a lot more demanding than just not cheating them (although obviously it includes not cheating them as a consequence!).

Where did this broader requirement come from? I think there are two sources.

One source is that our market today is defined by competition. Of course competition existed before now, but today it is presupposed as a fundamental rule of economic engagement in a way that seems more pervasive than earlier.

(By way of contrast, consider the—fictional!—motto of Ralph's Pretty Good Grocery from Garrison Keillor's A Prairie Home Companion: "If you can't find it at Ralph's, you can probably get along (pretty good) without it." Naturally this was never the explicit motto of any real store. But the joke wouldn't have been funny if there had never been a time or place when a shopkeeper might have thought such a thing. Nor would it have been funny if people still believed it today.)

The other source comes from a major demographic shift in the developed world. In 1790, 90% of Americans lived on farms, and necessarily practised some measure of self-sufficiency. They largely made their own tools and their own clothes. Of course you could buy things, and people did. But for everyday items it was often more economical to make your own.

By 2019, in contrast, that same fraction was 1.4%. And the majority of people who live on farms today are specialists—as farmers—rather than generalists. Even those who still know how to make their own tools and clothes largely don't do it, because it is cheaper to buy them. Also, most farms produce crops for sale rather than for subsistence. Because of massive improvements in transportation and communication, and because of the corresponding changes in the overall economy which those improvements have driven, self-sufficiency is no longer assumed. The consequence is that today, we are all customers! Everybody is a customer of somebody else, or rather many "somebodies."

I argue that these two changes—the pervasiveness of competition and the universality of the customer-relationship—have changed the nature of Customer focus. Once upon a time, all you had to do for your customers was to be honest and fair with them. Now you have to do more, both because your competitors are doing more (so you have to keep up) and because you yourself are a customer (and so you want to encourage your suppliers to treat you well in turn).

So is Quality a modern concept after all?

Yes and no. Mostly yes.

Everything I wrote at the beginning of this post—about Plato and Hammurabi and the rest—is still true. It is still true that people have known the difference between good work and bad work as long as people have been doing work.

But Quality as we understand it today is a concept rooted in late-stage capitalism. It relies on five developments that are indisputably modern:

- an understanding of business processes that was possible only after a century of industrialization;

- an understanding of statistics that grew out of work done in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries;

- the spread of corporations as the default organizing unit of the labor economy;

- the assumption of competition as the pervasive principle of the market;

- and the integration of everyone into that market, so that the supplier-customer relationship became universal.

That's why we are still today refining the conceptual framework that supports Quality. The modern understanding of Quality truly is modern, because it incorporates and builds upon social and intellectual developments that have made our modern day different from every age that went before.

__________

* There is no general principle of product liability stated explicitly in the Code of Hammurabi, but there are specific provisions from which a common principle can be inferred. For example:

229. If a builder build a house for a man and do not make its construction firm, and the house which he has built collapse and cause the death of the owner of the house, that builder shall be put to death.

233. If a builder build a house for a man and do not make its construction meet the requirements and a wall fall in, that builder shall strengthen that wall at his own expense.

235. If a boatman build a boat for a man and he do not make its construction seaworthy and that boat meet with a disaster in the same year in which it was put into commission, the boatman shall reconstruct the boat and he shall strengthen it at his own expense and he shall give the boat when strengthened to the owner of the boat.

For the complete text, see The Code of Hammurabi (Harper translation) - Wikisource, the free online library.

** In the Hippias Major, Plato has Socrates ask Hippias about the meaning of τὸ καλόν, often translated "the Beautiful," or "the Fine." Hippias first argues that you make something fine by making it out of gold and ivory. But Socrates points out (290D) that for a kitchen spoon to stir soup, it's better to make it out of wood. In this way he gets Hippias to agree that the Fine is "the appropriate." (293E) By similar arguments, he suggests that the Fine is "whatever is useful" (295C), "the useful and able for making some good" (296D/E), and finally "what is pleasant through hearing and sight" (298A). I think it is remarkable that Plato comes so close to modern definitions of Quality such as Crosby's "conformance to requirements" or Juran's "fitness for use." (Compare this post here.) All the same, he never develops a theory of Quality itself, as we understand the term today.

*** See, e.g., Gregory H. Watson and John R. Dew, "The Reality of Process: The influence of Alfred North Whitehead on quality thinking," in Quality Progress, Volume 55 Issue 2, February 2022, pp. 28-33.

**** Note that these two principles are linked together because each entails the other. Leadership is meaningless unless there are people engaged who are being led. Conversely, if people are engaged with each other in a common task, then usually there is already a leader—open or hidden—around whom they have coalesced; in the rare cases where a group coalesces without a clear leader, one emerges right quick.